Tomorrow, Saturday February 1st 2014, the

University of Kent Keeley

Saunders , Frances

Greenaway has been vocal on the subject of cinema’s

limitations for many years, most overtly in his insistence that cinema has

never developed into its own visual

medium, and that it’s reliance upon the written word (in the form of

screenplays) makes it a slave to the earlier traditions of literature and the

theatre. He believes that cinema, in order to free itself from the constraints

of text, should become an entirely audiovisual medium, closer to a moving

painting than a performed story. Despite this attitude, Greenaway himself has

produced little work in this vein, instead choosing to produce work that critiques existing cinematic conventions

rather than providing alternative ones.

Not to say that he has produced nothing that moves beyond the parameters of standard film; there is

the multi-screen VJ performances of The

Tulse Luper Suitcases, where he edits the film ‘live’ on stage, or the

installation work Peopling The Palaces,

that projects film on to all of the walls and even ceiling of a particular

venue, providing an immersive cinematic experience, or his projection of light

onto Rembrandt’s The Night Watch in

order to make the painting appear to move and transform. But his most well

known works (The Cook, The Thief, His

Wife & Her Lover, The Pillow Book,

Drowning By Numbers or Nightwatching) are feature-length

narrative films that began life as screenplays. These films often provide

alternative ways of presenting story information other than through traditional

narrative; Drowning By Numbers is

structured numerically, with the numbers 1-100 littered through the film

counting down to the conclusion, Cook/Thief/Wife/Lover

structures its characters and events around the conceit of Newtonian colour

theory, with each set designed around a different colour and its apparent

associated meanings. But most frequently, Greenaway’s favourite alternative

structure to narrative is that of lists and categories.

M Is For Man, Music

And Mozart is a 30 minute short film (part of the series Not Mozart where famous directors and

composers deconstruct the works of Mozart) that demonstrates Greenaway’s

obsession with the cinematic image, its relationship to text and theatre, its

potential to replicate painting and become a chapter in the history of Visual

Arts, and the use of categories, lists and associations as alternative devices

to narrative. Ostensibly, the film is a meditation on Mozart and his music

through a series of short segments, each building upon the last and providing a

slightly different structuring device. It opens with a list of words, written

and sung in largely alphabetical order, presenting a variety of concepts

related to man, his body (B is for bile, blood and bones) and beliefs (A is for

Adam, E is for Eve). As these words appear across the screen, two female dancers

(who might be muses, fates, furies, or stage-hands) communicate the ideas

through their bodily movements in a blacked-out space, filled in by sketches

and words superimposed on screen.

Once the alphabet has reached the middle letter, ‘M’, an

allegorical tale begins, showing the gods creating man. The gods, a shifty

looking crowd of corpse-white individuals wearing rags and holding various

signs marked with single words, proceed to try and make a ‘man’, going through

various possible source materials. Now the film utilises a ‘theme and

variation’ structure: a Man of Letters is a human outline created from the

gods’ signs, a Man of Meat is cobbled together from a butcher’s wares, a Man of

Metal is comprised of various utensils, and so on. These proto-men are

Acrimbaldo-like figures, simultaneously a human-like entity and a collection of

objects.

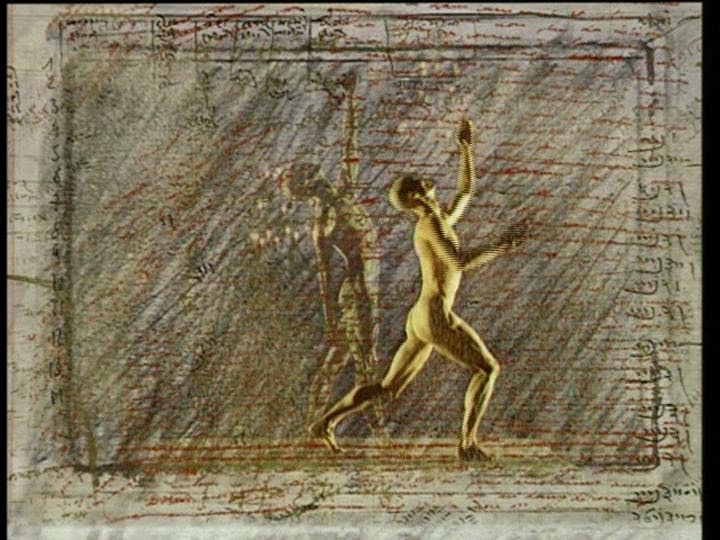

Eventually, Man as we know him is finished and a new

sequence begins where the gods teach man movement. An extended dance sequence functions

as a demonstration, as Man slowly at first moves his arms and legs, eventually

getting up and dancing about the auditorium where the action takes place. In

the next sequence, the gods teach Man music, and another dance sequence sees

the two maybe-muses manipulate Man like a mannequin, moving him in rhythmic

actions and placing various instruments in his hands. Finally, having created

man and music, the gods find it necessary to create Mozart and another sequence

mirroring the first sees Man in a blacked-out space embellished with hand-drawn

sketches and notes.

But Greenaway twists this relationship in order to give visuals the upper-hand. Long fascinated with calligraphy, the art of penmanship where the craft is in the very specific visual flourishes of letters, Greenaway transforms text into images, the words do not overcrowd or block out the visual composition, but instead become a part of it. Though there remain layers and layers of complex word-games and associations going on within the words on screen, our attention instead is pulled towards the visual qualities of the words, their aesthetic worth within the overall framed composition.

M is not only the first letter in Mozart’s name, it is also

a symmetrical letter, sitting in the centre of the frame (as it sits in the

centre of the alphabet), it calls attention to and aids the balance of the

composition, further emphasised through the similarity of the two muses/stage-hands

that cavort throughout the film. Likewise, the scroll of writing that runs

along the top of the screen, like a news report, simply reiterates words that

have been sung earlier. These words are included because of how they look and

what they add to the film’s visuals rather than as communication of new

information.

As stated above, we can find these sorts of text-image

relationships in an earlier tradition, that of the illuminated manuscript. One

can find a plethora of illuminated books from the 13th century onwards that

augment the written words of the Bible with ornate images that do more that

simply illustrate the story, but I wish to focus on two much later examples.

William Blake, famous for providing illustrations to the Bible, Milton

Linking in with the previous month’s post on Wunderkammer’s,

the illuminated work The Model Book Of

Calligraphy belonged to the eccentric Emperor Rudolph II. Initially a book

consisting entirely of calligraphy by Georg Bocksay, Rudolph II commissioned

artist Joris Hoefnagel to provide paintings to accentuate the visual beauty of

the words. Hoefnagel not only provided images that related to the words already

on the page but also composed them in such a way as to create apparent spatial

relationships between word and image. The text, originally laying flat on the

page, now seems to float in the air, hovering above the flora and fauna that

appear grounded on an ambiguous surface. New images, depicting specific

objects, transform the nature of the images of text. Not simply illustration,

where the images are limited to the content and meaning of the words, but a

visual response to the text,

Hoefnagel’s illuminations prefigure Greenaway in their combination of text and

image in service of aesthetic rather

than informative purposes. These images have been taken from three volumes

published Thames & Hudson, annotated by Lee Hendrix and Thea

Vignau-Wilberg. Unfortunately, there are few images available online and so

these are photos of the books taken by my own fair hand – hence the slightly

poor quality.

The latter portion of the same book allows Hoefnagel to take

this even further, producing an ‘Abecedarium’, an artistic guide to the letters

of the alphabet. Here, the letters form the central focus of each image, but

they are also the foundation of a visual work, it is their artistic qualities

that are emphasised. Both the ‘majuscules’ (capitals) and ‘miniscules’

(lower-case) are presented to us in glorious elaboration, the symmetrical

composition and rich detail of the depicted objects again creating a sense that

we are seeing a three-dimensional construct in space rather than a flat image

on a page.

This is the same effect that Greenaway achieves, though through the exact opposite means. While Hoefnagel takes the flattened words and letters of text and places them within a fictional space through the application of artistic depictions, Greenaway takes the actual space of the pro-filmic action – the auditorium and space where the figures move, create and dance – and uses overlaid text to flatten the images on screen. The images and text are united in a conceptual middle-ground; in Hoefnagel’s work, they do not meet on the page but the space depicted within it, and in Greenaway’s film the diegetic space of the action seems to collapse into the non-diegetic superimposed text to create a composition that exists on the screen. In both cases different artistic media have been merged in the creation of something new.

- P.S.

This is the same effect that Greenaway achieves, though through the exact opposite means. While Hoefnagel takes the flattened words and letters of text and places them within a fictional space through the application of artistic depictions, Greenaway takes the actual space of the pro-filmic action – the auditorium and space where the figures move, create and dance – and uses overlaid text to flatten the images on screen. The images and text are united in a conceptual middle-ground; in Hoefnagel’s work, they do not meet on the page but the space depicted within it, and in Greenaway’s film the diegetic space of the action seems to collapse into the non-diegetic superimposed text to create a composition that exists on the screen. In both cases different artistic media have been merged in the creation of something new.

- P.S.